COVID-19 and its effects

To contain the spread of COVID-19, many countries implemented social distancing measures, enacted stay home orders, and had nation lockdowns to encourage citizens to minimise contact with others (Banerjee & Rai, 2020; Javed et al., 2020). These self-isolating strategies may have protected people from the pandemic physically, but they also brought a slew of issues. Research done on outbreaks and pandemics that happened before shown that both social isolation and loneliness have detrimental psychological effects on the population (Razai et al., 2020). Social isolation and loneliness have been issues of concern before the pandemic, but the implementation of these self-isolating strategies exacerbated the spread of social isolation and loneliness in vulnerable communities (Banerjee & Rai, 2020; Hwang et al., 2020; Salerno et al., 2020).

LGBTQIA++, social isolation and loneliness

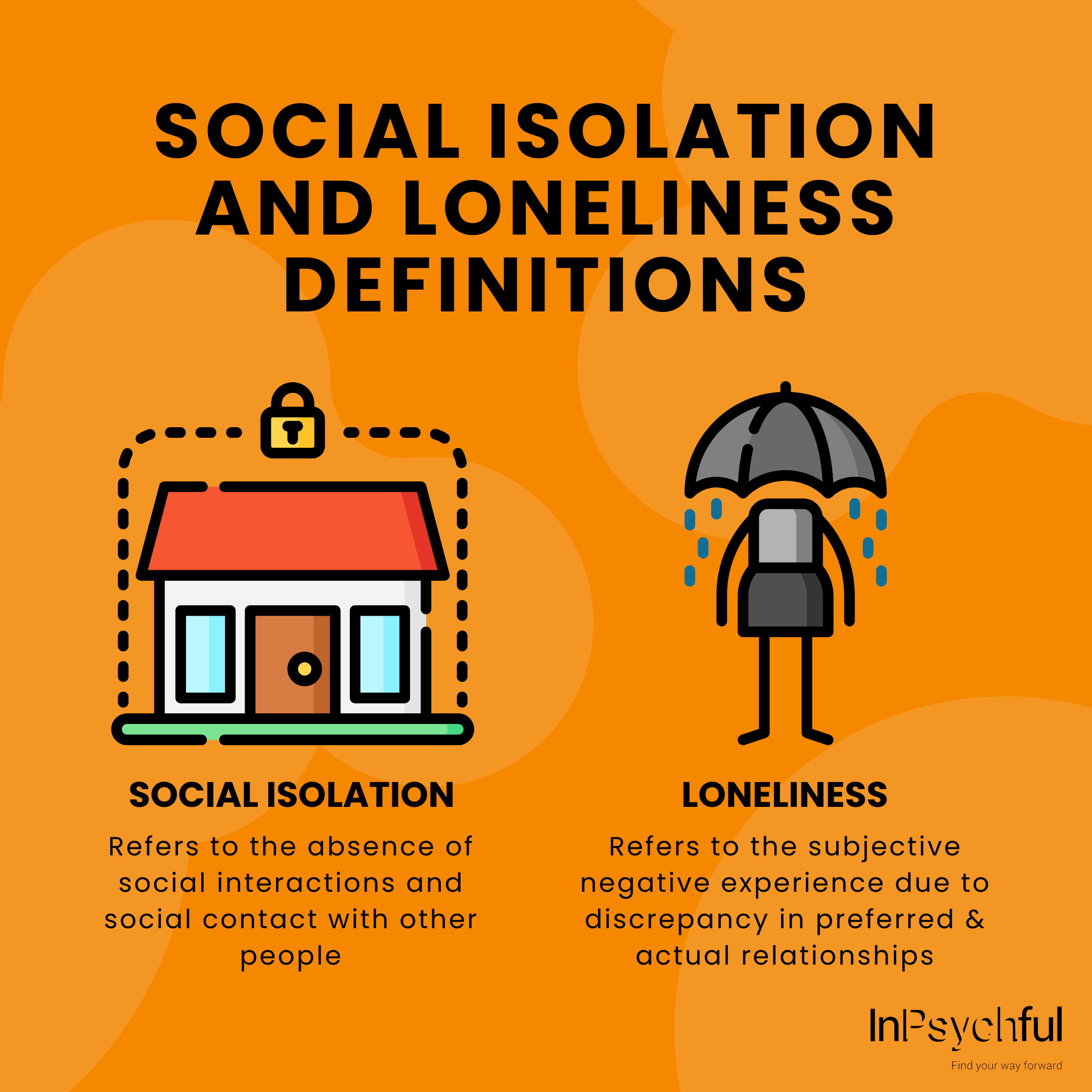

As a community that is prone to social isolation and loneliness due to historical and social discrimination pre-COVID, it is important to identify the additional stressors that an LGBTQIA++ individual might face during this pandemic to provide better support for their mental health (Peterson et al., 2020; Suen et al., 2020; Tomar et al., 2021). When a person’s perceived social relationship does not match what they have desired, this discrepancy leads to the negative experience of feeling alone (Cacioppo et al., 2015). Social isolation, on the other hand, refers to the absence of social interactions and contact with other people (Cacioppo et al., 2015). While feeling lonely does not mean that you are socially isolated and that one may feel socially isolated even amongst friends and family, both social isolation and loneliness can have several negative impacts on one’s health. (Cacioppo et al., 2015; Hwang et al., 2020; Razai et al., 2020). Studies have shown that both social isolation and loneliness are significant predictors of negative health outcomes, such as higher rates of mental health disorders, suicide ideation, substance use as well as risky sexual behaviours (Garcia et al., 2019; Yadegarfard et al., 2014). For this reason, it is important to understand and be aware of the additional stressors that LGBTQIA++ individuals face so that efforts can be made to reduce the occurrence of social isolation and loneliness.

What are some of the additional stressors an LGBTQIA++ young adult face?

While COVID has brought about massive disruption in everyone’s lives, there are specific stressors that affect those who are in the LGBTQIA++ community (Banerjee & Nair, 2020; Suen et al., 2020). The list in this article is not comprehensive by any means but it gives a general overview of some of the additional stressors that an LGBTQIA++ individual might face. These stressors include fear of being ‘outed’, shrinking of physical “safe spaces”, having to live in hostile non-affirming family environments, as well as reduced contact with “chosen families” (Nicholas et al., 2020).

Fear of being ‘outed’

Being ‘outed’ or forced to ‘come out of the closet’ is the deliberate or accidental disclosure of an LGBTQIA++ person’s sexual or gender identity without consent (Guzman, 1995). For many LGBTQIA++ individuals, having a choice taken away from them may feel grossly invasive and overwhelming. Due to social distancing measures and nation lockdowns, most of the LGBTQIA++ physical events had to be moved to online platforms or risk being cancelled. Organisations in Singapore, such as Sayoni, Pink Dot and Prout, embraced technology to work around the COVID restrictions by organising webinars, online trivia nights and an upsized livestream programme (Khalid, 2020). While these are helpful in maintaining a sense of community during these trying times, those that are still not open about their sexual identities have to risk being ‘outed’ if they were discovered accessing these virtual platforms at home (Nicholas et al., 2020). For the queer individual who had to deal with facing possible eviction, homelessness, and abuse if they were ‘outed’ during this pandemic, this fear may then result in the individual choosing not to access these virtual platforms, increasing the likelihood of social isolation and loneliness.

Shrinking of physical “safe spaces”/ safe spaces no longer safe

With the shrinking and destruction of physical ‘safe spaces’ to explore and express their own sexual identities without judgement, LGBTQIA++ individuals face the risk of being more social isolated and feeling more alone compared with their heterosexual counterparts. Worldwide, LGBTQIA++ friendly bars and clubs had to close or have reduced opening hours due to the COVID restrictions (Savage et al., 2020). The closing of schools and institutions as well as the restriction of neutral spaces due to COVID also meant that there is a reduction of safe spaces for young adults who are navigating their sexual identities (Nicholas et al., 2020). In addition to the shrinking of ‘safe spaces’, ‘safe spaces’ may no longer be safe for the LGBTQIA++ community to go to. In South Korea, a detailed log of an infected person’s age, neighbourhoods and travel movements will be sent out by the city or the district as an alert to those that are living nearby (BBC News, 2020). After it was reported that an infected man had visited some gay bars at Seoul’s nightlight district, news outlets in South Korea published the names, addresses and workplaces of men who have tested positive for the virus (Kim, 2020). In Japan, customers of gay bars worry that contact tracing could reveal their sexual identities and ‘out’ them, so they are choosing to stay away (Lies, 2020). These physical ‘safe spaces’ are usually where the LGBTQIA++ go for social support and resilience from the community (Banerjee & Nair, 2020). As a result, the reduction and disappearance of ‘safe spaces’ may inadvertently worsen the situation on social isolation and loneliness.

Living in hostile non-affirming environments

Due to nation lockdowns, LGBTQIA++ individuals may have to stay in hostile non-affirming environments during the COVID pandemic. A study done on nationally representative survey data from Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam found that there are moderate to high levels of homonegativity despite the increase of LGBT visibility globally (Manalastas, et al., 2017). With the government sanctioned nation lockdowns and social distancing measures in place, LGBTQIA++ individuals may be stuck in a situation where they cannot remove themselves from hostile non-affirming environments and seek support outside. A study on LGB youths in Hong Kong had reported that participants are experiencing family conflict in relation to their sexual orientation during the COVID pandemic as they had to stay home more often than before (Suen et al., 2020). The researchers compared the result of this study with another similar study that was done pre-COVID and found that the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms have increased amongst LGB youths (Suen et al., 2020). A shelter for homeless LGBTQ people in Singapore also reported having a waiting list of people asking to stay there due to the increased discrimination and abuse amidst the COVID restrictions (Teng, 2020). Having to constantly confront the fact that the LGBTQIA++ individual’s actual relationship with the members in the household is not what they desired, it is not difficult to conclude that this stressor is an important predictor of social isolation and loneliness.

Loss of support networks/ “Chosen family” support

It is suggested that ‘chosen families’ emerged as a response to the social stigma that LGBTQIA++ individuals face (Gates, 2017). LGBTQIA++ individuals usually form support networks of ‘chosen families’, which refers to the formation of nonbiological kinship bonds chosen for the sole purpose of mutual support and love (Gates, 2017). Research results have suggested that having a strong social support serves as a mediating buffer against negative health outcomes for LGBT youths (McDonald, 2018), LGB elderly (Grossman et al., 2000), gay and bisexual HIV+ individuals (McDowell & Serovich, 2007) and transgender people (Trujillo et al., 2016). Research also suggest that social support and resilience are protective factors on mental health during the COVID pandemic (Li, et al., 2021). However, the implementation of strict COVID measures meant that the connection with the LGBTQIA+ community and ‘chosen family’ members is severely disrupted (Banerjee & Nair, 2020; Suen et al.,2020). Moreover, individuals who are ‘in the closet’ and living in hostile non-affirming environments may also face difficulty in managing romantic relationships with their significant others without raising suspicion of family members and thereby increasing the risk of being ‘outed’. The reduction in social interactions with their ‘chosen families’ and significant others during this pandemic may then result in increased feelings of social isolation and loneliness.

How can I maintain sanity amidst this chaotic world?

Resilience refers to one’s ability to maintain or regain mental health in the face of adversity, trauma, threats, and stress (Goldbach et al., 2020). Building resilience can help to cushion the negative impacts of social isolation and loneliness. This is supported in a study that found that having more resilience buffered the negative impacts of pandemic related stressors on mental health (Li, et al., 2021). Another study found that higher levels of resilience can help mitigate impacts of COVID-19 on anxiety and other health indicators amongst the LGBTQ+ population (Goldbach et al., 2020). So how can one go about building resilience and maintaining personal calm amidst this chaos?

Staying connected with others

The first step is to prioritize your relationships with others who support building resilience. While it may be difficult for those who are not open about their sexualities, choosing to socially isolate yourself during the pandemic will have severe consequences on your mental health. Try to stay in touch with your ‘chosen family’ and seeking help or support from the LGBTQIA++ community can help you build resilience. If possible, you can also try to find and join local LGBTQIA++ organisations that can offer you social support and a sense of purpose during this pandemic.

Developing a healthy self-care routine

Next, taking some time to reflect and create your self-care plan can help to prepare your body and mind to adapt to stress and reduce the impacts of negative emotions. A self-care routine is made up of a set of strategies or behaviours that can help you manage your stress levels as well as maintain a healthy mental state. Different people have different approaches to self-care, some positive and some not so positive. It is important to remember that a self-care plan is not a ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution and that you can revise your self-care plans depending on the different circumstances that may impact your life. So, what are the different kinds of self-care routine can one get into?

A recent study found that the self-care behaviours a sexual minority individual might engage in during the pandemic can be divided into 5 broad categories. The categories include managing relationships with others, setting routines that supports a positive wellbeing, maintenance of physical well-being and self-esteem, pursuing creative passions to rest and relax and lastly escapism or tuning out (O’Brien et al., 2021). While tuning out and engaging in escapism methods may provide temporary relief for the individual, it raises concerns of well-being over time (O’Brien et al., 2021). Escapism through unhealthy means is like slapping a plaster onto a festering wound, the wound will not heal properly and may worsen in the long run. Therefore, it is important to focus on developing healthy self-care routines instead of turning to negative outlets so that you can maintain a healthy body and mind.

Find purpose

The third step that you can engage in to build resilience is to find a purpose to believe in (American Psychological Association, 2012). You can find purpose through helping others, or even going through a journey of self-discovery. Helping others, be it through volunteering or lending a listening ear to someone in need, can help to foster a sense of self-worth and empower you in your journey to build resilience. Finding purpose in your own self-discovery journey can also help you to build resilience. While acknowledging that COVID is tough is helpful, it is imperative that you also consider what you can do next. Taking steps and being proactive in trying to reduce social isolation and loneliness yourself can help you develop resilience. You can also try developing realistic goals and making small steps to accomplish it. Reflecting on how much you have accomplished so far during this pandemic can also lead you to discovering that you have more strength in you than you are aware of.

Embracing healthy thoughts

“No one understands how isolated and alone I feel during this pandemic.”

Have you ever had these thoughts? These unhealthy thoughts can affect how you feel, and in the long run impact your levels of resilience. By identifying these irrational thoughts and changing your response to the stressful events, it can help to prevent you from feeling overwhelmed and helpless (American Psychological Association, 2012). By embracing in healthy thoughts and being aware that change inevitable for everyone, this positive outlook can help you feel better when you find yourself dealing with difficult situations. In addition to maintaining a positive outlook, reflecting on your past actions and thoughts can also help you develop a positive outlook if you were to face the same situation in the future.

Seeking help

While using the above strategies may help some develop resilience during this pandemic, it is also important to note that there is no shame in engaging a psychologist if you need help to develop appropriate resilience strategies for yourself. One of the ways that you can seek help during this pandemic while under nation lockdowns or strict stay-home orders is to find psychologists that offer e-therapy services. Zoom fatigue may be an issue for some, but it is better to have an option to seek help than to have no alternatives at all. Clients should note that E-therapy is only a viable alternative if they have a ‘safe space’ to conduct therapy.

E-therapy is the process of having a therapy session between a therapist and client through the utilization of electronic means to communicate with each other (Manhal-Baugus, 2001). While it was meant as a mode of therapy for those that are remote locations previously, there is discussion that this can be used as a temporary alternative to face-to-face therapy during the pandemic. Research have found that teletherapy can help to reduce the psychological effects of social isolation (Luiggi-Hernández & Rivera-Amador, 2020). E-therapy is an attractive option during this pandemic due to increased flexibility, reduction in travel time as well as having more effective therapy sessions (Feijt, et al., 2020).

As queer individuals, these additional stressors that you face during this COVID pandemic might be more than what your heterosexual counterparts are experiencing. Being ‘outed’, facing the shrinkage of ‘safe spaces’, having to live in hostile non-affirming environments and losing social support networks can increase the levels of social isolation and loneliness in the LGBTQIA++ community. However, it is important to note that you cannot always control your environment, but you can control how you think and feel it. Focusing on developing your resilience and building on your self-care routine, with the support of loved ones and trusted professionals, can help you be better prepared and face the challenges that may come your way.

Camillia Thng, BA., Camellia Wong, MA.

References

American Psychological Association. (2012, February 1). Building your resilience. American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/topics/resilience

Banerjee, D., & Nair, V. S. (2020). “The untold side of COVID-19”: Struggle and perspectives of the sexual minorities. Journal of Psychosexual Health, 2(2), 113-120. https://doi.org/10.1177/2631831820939017

Banerjee, D., & Rai, M. (2020). Social isolation in Covid-19: The impact of loneliness. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(6). https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020922269

BBC News. (2020, March 5). Coronavirus privacy: Are South Korea’s alerts too revealing? BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-51733145

Cacioppo, S., Grippo, A. J., London, S., Goossens, L., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2015). Loneliness: Clinical import and interventions. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 10(2), 238-249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615570616

Feijt, M., Kort, Y. d., Bongers, I., Bierbooms, J., Westerink, J., & IJsselsteijn, W. (2020). Mental health care goes online: Practitioners’ experiences of providing mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(12), 860-864. http://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0370

Garcia, J., Vargas, N., Clark, J. L., Álvarez, M. M., Nelons, D. A., & Parker, R. G. (2019). Social isolation and connectedness as determinants of well-being: Global evidence mapping focused on LGBTQ youth. Global Public Health, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2019.1682028

Gates, T. G. (2017). Chosen families. (J. Carlson, & S. B. Dermer, Eds.) The SAGE Encyclopedia of Marriage, Family, and Couples Counseling, 1, 240-242. https://www.doi.org/10.4135/9781483369532.n74

Goldbach, C., Knutson, D., & Milton, D. C. (2020). LGBTQ+ people and COVID-19: The importance of resilience during a pandemic. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000463

Grossman, A. H., D’Augelli, A. R., & Hershberger, S. L. (2000). Social support networks of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults 60 Years of age and older. The Journal of Gerontology, 55(3), 171-179. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/55.3.P171

Guzman, K. (1995, January). About outing: Public discourse, private lives. Washington University Law Review, 73(4), 1531-1600. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol73/iss4/2

Hwang, T.-J., Rabheru, K., Peisah, C., Reichman, W., & Ikeda, M. (2020). Loneliness and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(10), 1217–1220. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610220000988

Javed, B., Sarwer, A., Soto, E. B., & Mashwani, Z.‐u.‐R. (2020). The coronavirus (COVID‐19) pandemic’s impact on mental health. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 35(5), 993–996. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3008

Khalid, C. (2020, June 10). How the LGBTQ+ community in Singapore is staying connected. TimeOut. https://www.timeout.com/singapore/lgbtq/how-the-lgbtq-community-in-singapore-is-staying-connected

Kim, N. (2020, May 8). Anti-gay backlash feared in South Korea after coronavirus media reports. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/08/anti-gay-backlash-feared-in-south-korea-after-coronavirus-media-reports

Li, F., Luo, S., Mu, W., Li, Y., Ye, L., Zheng, X., . . . Chen, X. (2021). Effects of sources of social support and resilience on the mental health of different age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry, 21(16), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-03012-1

Lies, E. (2020, December 3). Battered but unbowed by coronavirus, Tokyo’s gay district forges stronger ties. Reuters. https://news.yahoo.com/battered-unbowed-coronavirus-tokyos-gay-010243158.html

Luiggi-Hernández, J. G., & Rivera-Amador, A. I. (2020). Reconceptualizing Social Distancing: Teletherapy and Social Inequality During the COVID-19 and Loneliness Pandemics. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 60(5), 626-638. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167820937503

Manalastas, E. J., Ojanen, T. T., Torre, B. A., Ratanashevorn, R., Choong, B. C., Kumaresan, V., & Veeramuthu, V. (2017). Homonegativity in Southeast Asia: Attitudes toward lesbians and gay men in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. Asia-Pacific Social Science Review, 17(1), 25-33. http://www.tinyurl.com/ybmug67r

Manhal-Baugus, M. (2001). E-therapy: Practical, ethical, and legal issues. Cyberpsychology & Behavior: The Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society, 4(5), 551-563. https://doi.org/10.1089/109493101753235142

McDonald, K. (2018). Social Support and mental health in LGBTQ adolescents: A review of the literature. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(1), 16-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2017.1398283

McDowell, T. L., & Serovich, J. M. (2007). The effect of perceived and actual social support on the mental health of HIV-positive persons. AIDS Care, 19(10), 1223-1229. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120701402830

Nicholas, L., Dernbach, P., Roca, G., Eastwood, N., & Rivers, G. F. (2020, May 7). The state of the LGBTQ+ community during the Covid-19 pandemic [webinar]. International Bar Association. https://www.ibanet.org/The-state-of-the-LGBTQ-community-during-the-Covid-19-pandemic#video

O’Brien, R. P., Parra, L. A., & Cederbaum, J. A. (2021). “Trying my best”: Sexual minority adolescents’ self-care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(6), 1053-1058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.03.013

Peterson, N., Lee, J., & Russel, D. (2020). Dealing with loneliness among LGBT older adults: Different coping strategies. Innovation in Aging, 4(Suppl 1), 516–517. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igaa057.1667

Razai, M., Oakeshott, P., Kankam, H., Galea, S., & Stokes-Lampard, H. (2020, May 21). Mitigating the psychological effects of social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. TheBMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1904

Salerno, J. P., Williams, N. D., & Gattamorta, K. A. (2020). LGBTQ populations: Psychologically vulnerable communities in the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S239–S242. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/tra0000837

Savage, R., Lavietes, M., & Anarte, E. (2020, May 13). ‘We’ll die’: Gay bars worldwide scramble to avert coronavirus collapse. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-lgbt-nightlife-trf-idUSKBN22P1Z5

Suen, Y., Chan, R. C., & Wong, E. M. (2020). Effects of general and sexual minority-specific COVID-19-related stressors on the mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people in Hong Kong. Psychiatry Research, 292, 113365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113365

Teng, Y. (2020, June 12). LGBTQ communities in Asia hit hard by pandemic restrictions. Yahoo!Style. https://sg.style.yahoo.com/lgbtq-communities-in-asia-hit-hard-by-pandemic-restrictions-122501473.html

Tomar, A., Spadine, M. N., Graves-Boswell, T., & Wigfall, L. T. (2021). COVID-19 among LGBTQ+ individuals living with HIV/AIDS: psycho-social challenges and care options. AIMS Public Health, 8(2), 303-308. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2021023

Trujillo, M. A., Perrin, P. B., Sutter, M., Tabaac, A., & Benotsch, E. G. (2016). The buffering role of social support on the associations among discrimination, mental health, and suicidality in a transgender sample. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(1), 39-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2016.1247405

Yadegarfard, M., Meinhold-Bergmann, M. E., & Ho, R. (2014, October 10). Family Rejection, social isolation, and loneliness as predictors of negative health outcomes (depression, suicidal ideation, and sexual risk behavior) among thai male-to-female transgender adolescents. Journal of LGBT Youth, 11(4), 347-363. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2014.910483