What is loneliness?

Have you ever felt this sense of loneliness, where you could be in a room full of people, yet you feel still alone deep within? Even when we are physically surrounded by other people, we can still experience loneliness (Cacioppo et al., 2009).

Loneliness is commonly defined as being alone or a state of solitude (Cherry, 2020). However, loneliness is more like a state of mind, rather than just being physically alone. Our perception of us being socially isolated and this discrepancy between what we desire from the relationship with our friends and family and our perception of it.

Despite having a large network of friends, the feeling of loneliness can still seep into our minds. There has been a discrepancy between the number of connections one has in their social network and the subject feeling of isolation (Berscheid & Reis, 1998). In other words, individuals still report feelings of loneliness, even with for those with extensive social networks.

Moreover, in a digital world today, the increasing use of social media may also have contributed to the perceived feeling of loneliness. Additionally, this pandemic has largely made more individuals feel more isolated, especially when there is physical isolation due to restrictions on social measures (Horigian et al., 2020).

Why may we feel this way?

There are several factors that can lead us to feel lonely, this includes environment, circumstances, and our thoughts, which are ways we think and feel about ourselves relative to the world (Psychalive, 2009). Additionally, the rampant usage of social media may also contribute to our perceived loneliness.

Thoughts

Humans are a social species, and we thrive and survive in social settings, which allows us to feel safe and secure (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2013). Our perception of loneliness and increased awareness of threat and feelings of being vulnerable can urge us to desire to connect with others.

When we feel lonely, which is similar to feeling unsafe, this can make us more vigilant about the additional social threats in the environment. We may start to develop some cognitive biases, seeing social settings as a more threatening place, expecting social interactions that are more negative and remembering more negative social encounters (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2013). We may be thinking about the times when our friends hung out without us and feeling left alone. This may then lead us to distance ourselves from others, as we believe that this social distance is not within our control. Eventually we can find ourselves in this self-reinforcing loneliness loop, where we may also feel stressed, pessimistic, anxious and hostile (Cacioppo et al, 2006).

A low self-esteem can also be an internal factor that is associated with loneliness. As individuals often believe that they are not valued and are not worth the attention and regard of others, leading to feelings of loneliness (Cherry, 2020).

Environment

Physical isolation or moving to an unfamiliar location can also contribute to the feeling of loneliness (Sbarra, 2015). With the COVID-19 pandemic, frontline workers such as those in the healthcare industry have reported feelings of isolation and loneliness (Lagoy, 2021). The implementation of restrictions to curb with the spread of COVID-19 has kept some of us home, away from our colleagues and friends.

Some may even feel lonely inside your homes, and this could be due to a lack of social connection with your family members (Higgins & Polish, 2016). With the Work-From-Home arrangement, lines between work and rest is blurred and this has a direct impact on families relationships. Even stay home mothers can feel lonely with their children as their days are filled with endless tasks to take care of their children, and this makes it easy for them to slide into isolation (Duncan, 2019).

Circumstances

Life is uncertain and it can be a very difficult experience to go through certain situations. Painful life circumstances such as divorce or can also contribute to the feeling of loneliness (Psychalive, 2009)

Social Media Influence

While social media allows us to connect with others more in the digital realm, it is causing us to become more disconnected from the real world around us. A study has found that even the presence of a mobile phone can cause individuals to experience less present enjoyment (American Psychological Association, 2018). However, when social media is used judiciously, there are certainly benefits which helps us to connect with others. For instance, social media connectivity can aid individuals with depression to seek resources and support, promoting recovery (Shalnna, 2018).

How loneliness can affect us

There is evidence which links perceived loneliness with adverse health consequences including depression, poorer sleep, impaired cognitive processes, poorer heart function and impaired immunity regardless of stages in life (Hawkley & Capitanio, 2015).

This feeling of loneliness is also correlated with depression and anxiety symptoms (Okruszek et al., 2020). Loneliness and social isolation can cause significant risk for premature death (Alcaraz, 2019). The lack of encouragements from loved ones may result in individuals sliding in unhealthy habits (Novotney, 2019). Research has also found that loneliness is associated with an increased risk of dementia (Sutin, 2018).

How can we manage this?

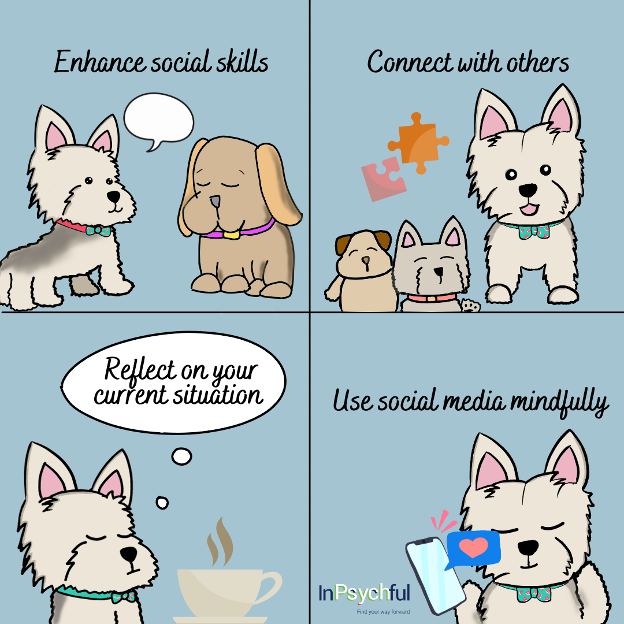

To manage such feelings of loneliness, there are a few approaches – namely, enhancing our social skills, providing social support, increasing opportunities for social interaction, and addressing our maladaptive social cognition (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2013). Managing our social media usage can also help us to alleviate the feelings of being alone.

Enhancing social skills

Some of us may feel more anxious or stressed during socialisation. While this may be a daunting task, it can be comforting to know that social skills can be practiced and developed. You can try practicing reflective listening and ask open ended questions which allows the other person to further explain and this would increase personal engagement (Higgins & Polish, 2021). Using physical non-verbal communication can show the other party that you are actively listening. Maintain the eye contact and nod to show that you are present with them.

Connect with others

It is the quality of the social interaction that helps to deal loneliness, rather than the quantity (Cherry, 2020). Who are the ones who you enjoy spending time with? List their names down and think about how you can feel less alone during lonely times. It could be reaching out to your close friends about how they are doing or finding an online community to chat.

You can also try having casual conversations with your friends or colleagues. Social connection can serve as a protective factor for our general and mental health (Walton, 2018). A Harvard study found that people with stronger social connections were the healthiest and happiest (Mineo, 2017). Try focusing on the ones who share similar attitudes, values and interests with you (Cherry, 2020).

Being involved in volunteering activities can be a great opportunity to meet people and build new friendships and social interaction (Cherry, 2020). Depending on the cause you are volunteer for, you may even meet likeminded individuals who share interest as you do! Studies have found that older adults who participate in social groups such as religious groups and book clubs have a lower risk of death (Steffen et al., 2016).

Reflect on our current situation and challenge how we view it

Ultimately, our minds are the most powerful weapon, and we can harness its strengths and use it to deal with our thought processes. Take some time to reflect on your current situation. What are other ways that we look at this situation? We can reframe our views about what it means to be alone. Some amount of quality alone time is also crucial. Such times allows for self-discovery, self-reflection, and creative thoughts (Klein, 2021). Being alone offers a great opportunity to become more aware of our emotions. Take this as an opportunity to sit down and get in tune with your feelings and goals (Klein, 2021).

Use social media mindfully

Lastly, try to reduce your usage of social media. It can be tempting to check your phone constantly to view updates from your friends and see what is going on in their lives (Higgins & Polish, 2021). However, we are not actively experiencing their lives with them which can further make us feel isolated. You may want to schedule some hangouts with your loved ones and friends to enjoy precious moments together.

To conclude, you may be reading this blog post because of feelings of isolation or you may want to extend your help to others who may be feeling lonely. We applaud you for taking that first step in managing this feeling. Moving forward, we can take small steps to reach out and interact with others to manage our emotions and to feel more connected again.

Authors: Camellia Wong (M.A), Tan Khai Teng

More Articles

Stuck at home and in the closet: COVID for the Queer individual (Social isolation/ Mental Health)

Reference

Alcaraz, K. I., Eddens, K. S., Blase, J. L., Diver, W. R., Patel, A. V., Teras, L. R., Stevens, V. L., Jacobs, E. J., & Gapstur, S. M. (2019). Social isolation and mortality in us black and white men and women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 188(1), 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwy231

Ali, S. (2018, Oct 5). Is Social Media Making You Lonely? Psychology Today.https://www.psychologytoday.com/sg/blog/modern-mentality/201810/is-social-media-making-you-lonely

American Psychological Association (2018, 10 August). Dealing with digital distraction. Science Daily. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/08/180810161553.htm

Berscheid, E., & Reis, H. T. (1998). Attraction and close relationships. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (), The handbook of social psychology (4th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 193–281). New York: McGraw Hill

Cacioppo, J. T., Fowler, J. H., & Christakis, N. A. (2009). Alone in the crowd: The structure and spread of loneliness in a large social network. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 977–991. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016076

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Ernst, J. M., Burleson, M., Berntson, G. G., Nouriani, B., & Spiegel, D. (2006). Loneliness within a nomological net: An evolutionary perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(6), 1054–1085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2005.11.007

Cherry K. (2020, March 23). The health consequences of loneliness. Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/loneliness-causes-effects-and-treatments-2795749

Cole, S. W., Capitanio, J. P., Chun, K., Arevalo, J. M. G., Ma, J., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2015). Myeloid differentiation architecture of leukocyte transcriptome dynamics in perceived social isolation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(49), 15142–15147. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1514249112

Duncan, A. (2019, Nov 13). Is It Possible to Be Lonely in a House Full of Kids? Very Well Family.

Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

Hawkley, L. C., & Capitanio, J. P. (2015). Perceived social isolation, evolutionary fitness and health outcomes: A lifespan approach. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1669), 20140114. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0114

Higgins M. & Polish J. (2021, May 20). Why You Feel Lonely Even When You’re Not Alone. Bustle. https://www.bustle.com/life/141491-5-reasons-you-feel-lonely-even-when-youre-not-alone-and-what-to-do-about

Horigian, V. E., Schmidt, R. D., & Feaster, D. J. (2021). Loneliness, mental health, and substance use among us young adults during covid-19. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 53(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2020.1836435

Klein, A. (2021, Apr 13). 12 Things to Do When You Feel Lonely. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/mental-health/how-to-not-feel-lonely#reframe

Lagoy, J. (2021, May 14). COVID-19 Loneliness. Psychiatric Times. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/covid-19-loneliness

Mineo, L. (2017, April 11). Good genes are nice, but joy is better. The Harvard Gazette. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2017/04/over-nearly-80-years-harvard-study-has-been-showing-how-to-live-a-healthy-and-happy-life/

Novotney, A. (2019, May) The risks of social isolation. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2019/05/ce-corner-isolation

Okruszek, Ł., Aniszewska-Stańczuk, A., Piejka, A., Wiśniewska, M., & Żurek, K. (2020). Safe but lonely? Loneliness, anxiety, and depression symptoms and covid-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 579181. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.579181

Raypole (2019, June 25). Is Chronic Loneliness Real? Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/mental-health/chronic-loneliness#causes

Steffens, N. K., Cruwys, T., Haslam, C., Jetten, J., & Haslam, S. A. (2016). Social group memberships in retirement are associated with reduced risk of premature death: Evidence from a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open, 6(2), e010164. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010164

Sutin, A. R., Stephan, Y., Luchetti, M., & Terracciano, A. (2020). Loneliness and risk of dementia. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(7), 1414–1422. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby112